As in many other fields, the role of women in the history of science has often been marginalized, sometimes hidden or unacknowledged. This is a problem of history, but also of current events, if it is true that we have just celebrated - on 11 February - the "International Day of Women and Girls in Science", established ten years ago by the United Nations General Assembly precisely to highlight the contribution of women in scientific subjects, and to bring to public attention the gap that still exists in many subjects between males and females in access to careers and even more so in career progression or in the leadership role in research groups. These issues go back a long way, and in recent decades scholars of the history of science have begun both to rediscover figures of women scientists who are little or not at all known, and to reflect on the role of these scientists in the history of scientific thought. We talked about women and science, in the past and present, with Elena Canadelli, professor of history of science at the University of Padua and curator of the exhibition “Cristina Roccati. The woman who dared to study physics”, which can be visited at Palazzo Roncale in Rovigo until 21 April.

Who was Cristina Roccati, the scientist to whom the exhibition is dedicated?

Cristina Roccati was born in Rovigo in 1732 and died in the same city in 1797. She is one of the few women who manage to undertake a course of study in the 18th century. She is the third woman in the world to graduate, after Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia in Padua and Laura Bassi in Bologna. Roccati attended classes at the University of Bologna, where she moved with her aunt and tutor, graduated in 1751, then frequented the scientific and cultural environment of Padua for a few months and finally returned to Rovigo. After an initial interest in poetry and literature, she chose a career in the field of natural philosophy, and went on to teach physics to her fellow citizens at the Accademia dei Concordi, an institution founded at the end of the 16th century to bring together scholars of literature, science and art. Roccati was the only woman elected president of the Academy. In a world without women, she managed to find her way.

He used the word 'choose' with regard to interest in physics. Was it possible for a woman in the 18th century to 'choose' a career?

The 18th century was still a very fluid context, in the sense that compared to, for example, the 19th century, the places and institutions where science was done were not yet fully established. Women started out mainly from a literary and humanistic culture, but there were some - a few - who went so far as to take an interest in scientific disciplines. It is also to be considered that areas that we now perceive as separate were actually connected: the two souls - humanistic and scientific - coexisted peacefully. And even after she dedicated herself to natural philosophy, Cristina Roccati still continued to take an interest in the humanities.

What are the main contributions you made to the scientific landscape of the time?

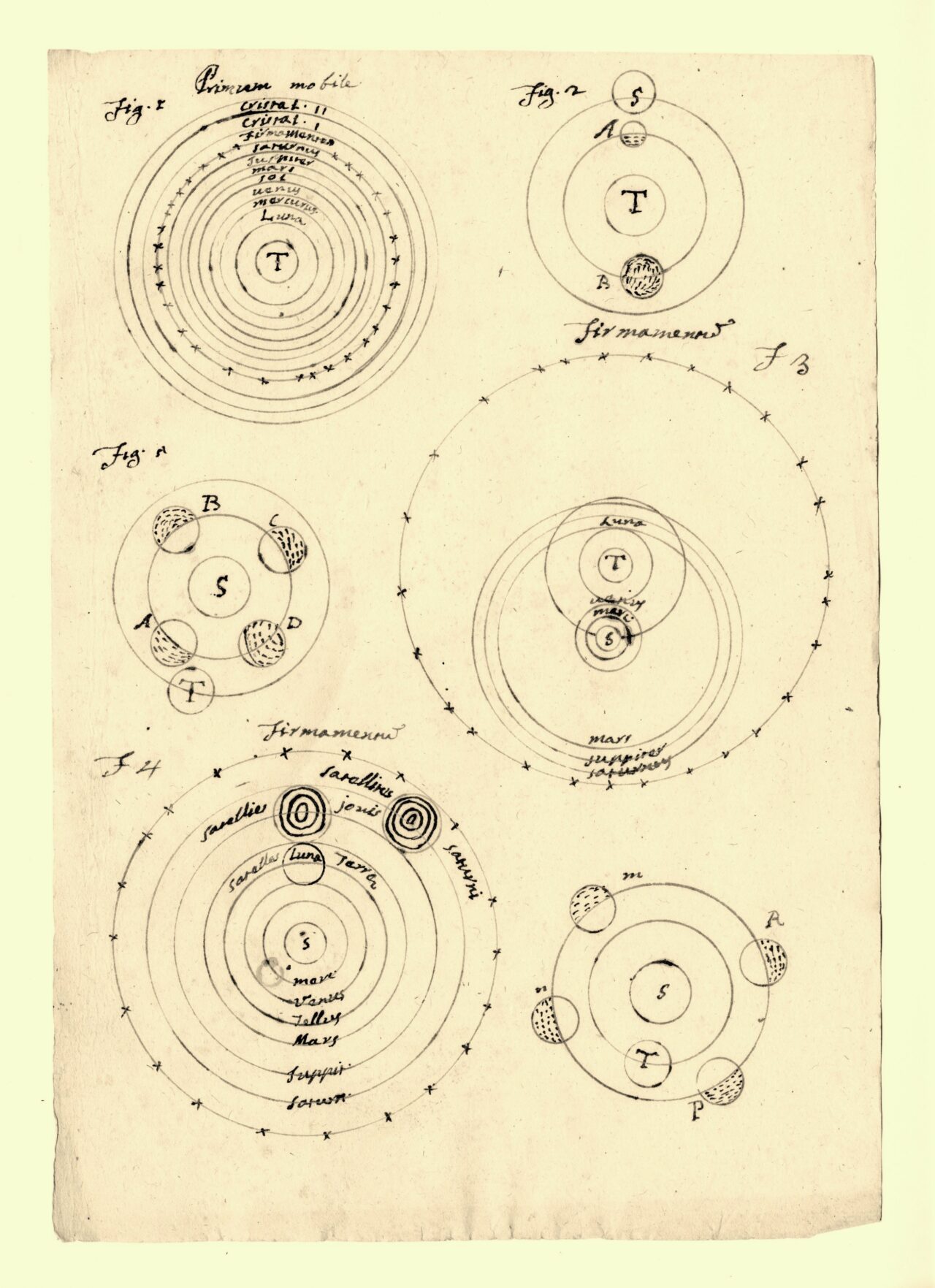

Roccati is active in the reception of Newton's works, in particular optics. We cannot call her a 'physicist', in the sense that she did not personally innovate this discipline, but in her lectures she circulated the ideas of Newton and his contemporaries, and contributed to the dissemination of the knowledge that was then being formed. She acts as a megaphone for the scientific culture of the time, for the physics between spectacle and science typical of the 18th century.

Were women exceptions or established presences in that context?

Roccati was the third woman in the world to graduate, in a world where there were no female students. In her acceptance speech for her graduation in 1751, she says 'I am the first - I hope - of a series of women graduates'. Women at that time were not allowed to enrol at university. Even in her role as a teacher, Roccati was an exception. It must be added that women were exceptions consciously used by the system as such. They were opportunities for families, institutions, society to put themselves on the map, real symbols. Although on rare occasions, the presence of women was allowed.

Why has his name fallen into oblivion, despite his significant role?

Cristina Roccati died a few months before the fall of the Venetian Republic, which corresponds to the fall of a world. In the ensuing turmoil, many years pass before she is commemorated, and it is possible that this contributed to her not being remembered. On the other hand, this is a fate common to many female scientists, who have passed into the background anyway. Only recently has historiography, first in the 1970s and then especially in the 1990s, rediscovered these figures. The exhibition serves to make people realise that there are many stories that have contributed to the making of knowledge in less sensational ways than is usual, and that the history of science is something different from the narrative centred only on great names.

What is the role of the historian and historian today in bringing these forgotten biographies to light?

Since the 1990s, there has been a recovery of these figures who have made a contribution, perhaps not exceptional, but nonetheless significant. The spirit of the exhibition is precisely to recount the lives and rediscover the biography of these women scientists, but also to talk about the problems of the past, which continue today, in the relationship between women and science.

Is there not a risk that 'rediscovering' at all costs the excellent women of the past will lead to the effect of perpetuating stereotypes and the image of a history of science made up of heroines, instead of heroes?

I often like to quote a passage from Anna Kuliscioff's 'The Monopoly of Man': 'Even if one were to cite an infinite number of women who distinguished themselves and on thrones and in the sciences and in literature, one would not get a spider out of the hole. The Sommerwill, the George Sand, the George Elliott, the Queen Elisabeths, are exceptions, they will tell me: and I, too, like to speak of the great unnoticed mass of women better than of those to whom no one denies that they have shown true superior ingenuity'. The risk of focusing only on the great figures, female rather than male, Marie Curie or Rita Levi Montalcini, is indeed there. As historians, all we can do is to tell the stories for what they are, to make people think about the making of the history of science, with all its protagonists. Before the 20th century, women's roles were mostly found in the interstices. As a historian of science, my aim is to show the complexity of the making of science and to provide elements for understanding why things went (or are going) a certain way instead of another.

Chiara Palmerini