How many of us have heard of theEncyclopédie, the work of Denis Diderot and Jean-Baptiste d'Alembert, and flagship of the French Enlightenment? And again: how many of us own, or have owned, at least one encyclopaedia in our homes? Almost everyone.

The Treccani (who certainly knows a thing or two about encyclopaedias) defines it as a "work in which notions of all disciplines or just one of them are systematically collected and ordered. The word comes from the Greek ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία, 'circular education, a set of doctrines forming a complete education'". Influenced by the history we learnt at school, almost all of us would take the recent, 'Enlightenment' nature of the encyclopaedia for granted. Instead, its history and origin can be considered much more distant, going back even to antiquity, and certainly to the Middle Ages. A complex set of roots that is still very little investigated.

With the project SPACE - The System of Philosophy in Arabic: Charting the Encyclopediasfunded with more than half a million euros from the first edition of the Italian Science Foundation (FIS), researchers from PhiBor of the IMT School are doing just that: gaining a greater understanding of the great adventure of medieval science, and Islamic science in particular, by highlighting the connections and bridges between cultures across the diverse world of the medieval Mediterranean, and beyond.

From the human desire to 'make order'...

The encyclopaedia stems from the desire of human beings to gather what they know, to put it together, to systematise it: a desire much older than the 18th century in which Diderot and d'Alembert lived. With the great Mesopotamian civilisations, starting with the Sumerian, the need to create lists of names for scholastic study soon arose along with writing. These lists were then often expanded, explaining what the names referred to. In classical antiquity, Aristotle embarked on the hitherto unattempted feat of embracing the whole of knowledge with rational knowledge. When antiquity itself was coming to an end, in the 5th century, two Latin writers unknown to the general public today, Macrobius and Martianus Capella, attempted, each in their own way, to create compendia of knowledge, both practical and philosophical, in order to preserve and transmit it. Two centuries later, Isidore of Seville (still the patron saint of scholars today) wrote a work significantly entitled Etymologiae o Origines, based on an intention very similar to that of Macrobius and Martian. In this work, the meanings of words, subdivided by domain (e.g. numbers, planets, institutions), were explained by reference to their (true or presumed) etymological origin.

... to the philosophical summa of Avicenna

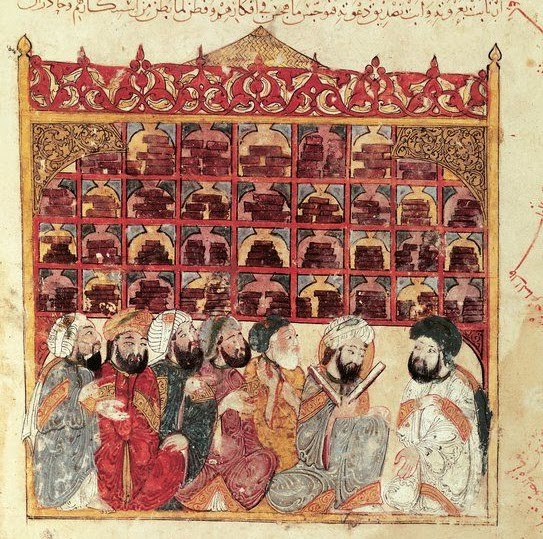

Yet no one, not even Aristotle, wanted or succeeded in connecting all this mass of knowledge in a truly systemic manner, and in addition to uniting it with new paths of research in order to achieve, as specified by the definition given above, a truly complete education. This was the task of the work of Ibn Sīnā, better known as Avicenna. This great scholar, originally from Buḫāra, in what is now Uzbekistan, and who lived between the end of the 10th and the first half of the 11th century, made a remarkable effort towards the systematisation of the scientific enterprise, at the same time recovering Aristotelian philosophy and thus realising not only the dream of a systematic and complete knowledge (within the limits, of course, of the means at his disposal) but also a veritable bridge between the philosophy of antiquity and that of the following centuries.

In other words, while we may not be able to give a clear-cut answer to the question of who is the inventor of the modern encyclopaedia, we can certainly consider Avicenna as one of the founding fathers of the concept itself as we understand it today. The main focus of the project SPACE is then Avicenna's main work, the Kitāb al-Šifāʾ, or Book of Healing, a massive encyclopaedia of its author's mature philosophical thought, comprising 22 distinct sections and over five thousand printed pages in the only complete edition available to date. These numbers are sufficient to give an idea of the vastness and monumentality of the work, but they alone are not enough to represent the complexity and depth of Avicenna's work. SPACE sets itself precisely this objective: to elucidate the relationships between the various aspects of knowledge, definitions, analyses, that Avicenna constructs in the Kitāb al-Šifāʾ.

The acronym of the project is thus anything but accidental: if the encyclopaedia is, in a sense, a mirror of the cosmos, a small cosmos itself, then the fundamental objective of SPACE is to map such a small cosmos, to give us an idea of its boundaries, its supporting structures, the connections that hold it together. It is hard to imagine a better way not only to do justice to what were Avicenna's intentions and goals, but also to understand how, well before the French Enlightenment, at the height of the Middle Ages, a veritable 'Lost Enlightenment' found fulfilment in Central Asia and the lands of present-day Iran, to borrow the title of a book by the American scholar S. Frederick Starr that is dedicated to it.