The profession of the archaeologist has always been incredibly multifaceted. Alongside the practical part of the excavation, the one that is certainly best known and most romanticized for its somewhat adventurous character, there is also a part that is perhaps less physically active, but certainly no less stimulating, that of research, which is carried out both before the excavation, as preparation, but also afterwards, as a study of what has been brought to light. Studying the past, however, certainly does not mean remaining anchored to the past. With the advancement of new technologies, archeology too has updated and kept up with the times: from research done in libraries and archives, writing with pen and paper, we have moved on to digitizing material online, taking notes on the computer. But that's not all: drones, radar, magnetometers, 3D technologies, Lidar cameras, GIS (geographic information system) have become an integral part of archaeological practice, both in its more theoretical aspect and in the practical one of fieldwork. Recounting how archeology has been transformed and what it is today is Nicolò Dell’Unto, professor at the University of Lund, Sweden, and director of the Lund University Digital Archaeology Lab.

What is meant by digital archaeology?

Today, knowledge is mainly generated in the digital world, not only as a means of writing and communication, but also of research. Many archives make their collections available online, facilitating access to documents and articles even without the need to physically go to the library; excavation data are digitised and, when possible, shared online, and museums too are moving towards digitisation. Therefore, some argue that one should not speak of "digital archaeology", as even traditional archaeology now operates in a digital space. However, this transition has deeply influenced archaeological theory. As early as the 1960s-1970s, there was talk of 'computational archaeology', which later evolved into 'digital archaeology' and became a discipline in its own right.

In 2006, Patrick Daly and Thomas Evans published Digital Archaeology: Bridging Method and Theory, initiating a more theoretical debate about the role of digital not only as a computational tool, but also as a reflexive one. Today, digital archaeology can be seen as a container that includes computational archaeology and other approaches. Personally, I think that this distinction will disappear and become an integral part of archaeology in general.

For me, digital archaeology perfectly represents contemporary archaeology, which moves between collecting data in the field and processing them digitally to generate knowledge. These data, transformed into digital objects, are reinterpreted and returned in the form of books, prototypes or new ideas. In short, it is a circular process that characterises the way we create and use archaeological information today.

How has digital archaeology changed the work of the archaeologist and what changes can we expect in the future?

Every archaeological datum is, in fact, a cultural construction: the way it is generated depends on the tradition of excavation and the methodologies adopted. With the introduction of digital tools, this process is undergoing a significant evolution. Whereas in the past, consulting archives required a physical presence, today there is an increasing shift towards digital data management, changing the way archaeologists access information and use it in research. It must be said that universities still do not adequately prepare students to work with digital archives, despite the fact that these are becoming essential to the discipline.

With James Taylor, in 2021, I wrote an article on skeuomorphism, analyzing how archaeological practices change through a phase of technological imitation. This phenomenon is visible, for example, in the initial use of photogrammetry: initially the photo from above was used as a basis for digitally tracing the map, thus replicating the traditional method. With time and the acquisition of familiarity with this new technology, it was possible to develop new applications that did not simply repeat the previous ones, but that surpassed them.

I believe that the introduction of artificial intelligence will be the next big change. The amount of data produced today exceeds the human capacity to handle it, as digital archives are no longer built on a human scale, but on a computational scale. A concrete example of the use of artificial intelligence in archaeology concerns the automatic classification of extremely complex information that is difficult to analyse manually. For instance, deep learning algorithms can be trained to recognise potential archaeological sites in satellite or lidar images, even in densely vegetated areas where the human eye struggles to detect traces on the ground. Another promising area is the automatic analysis of handwritten texts: platforms such as Transkribus use AI to transcribe and interpret medieval historical documents, facilitating the consultation of archival sources that are difficult to access.

AI will thus become a mediator between researchers and data, facilitating the navigation and interpretation of information. The main challenge will be to ensure an ethical use of these technologies. AI learns from the data it is given, and if certain perspectives or communities are excluded from the reference datasets, the risk is that they will also be rendered invisible in future research. The problem is not the AI itself, but the way we train and use it. Therefore, the future of archaeology will have to involve a critical and conscious integration of these technologies, so that they can truly support the discipline without distorting its purpose.

Is archaeology today a humanistic science or an exact science?

These categories are often more conventional than real. An archaeological excavation is a unique and unrepeatable event, but this does not mean that archaeology cannot adopt quantitative methods or advanced analytical tools. The use of computational models, statistical analysis and digital tools does not alter the nature of the discipline, but expands its possibilities of investigation.

Today, one does not need a background in physics to use a GIS, just as one does not need to be a programmer to manage an archaeological database. At the same time, knowing programming languages does not guarantee a better understanding of archaeological data. This distinction between the humanities and the sciences therefore seems artificial to me, similar to the division between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age: useful by convention, but not so clear-cut in reality. We are in an experimental phase that, although complex, is extremely stimulating and opens up new perspectives for the discipline.

You are the director of DARKLab. What are the most significant projects you have been involved in?

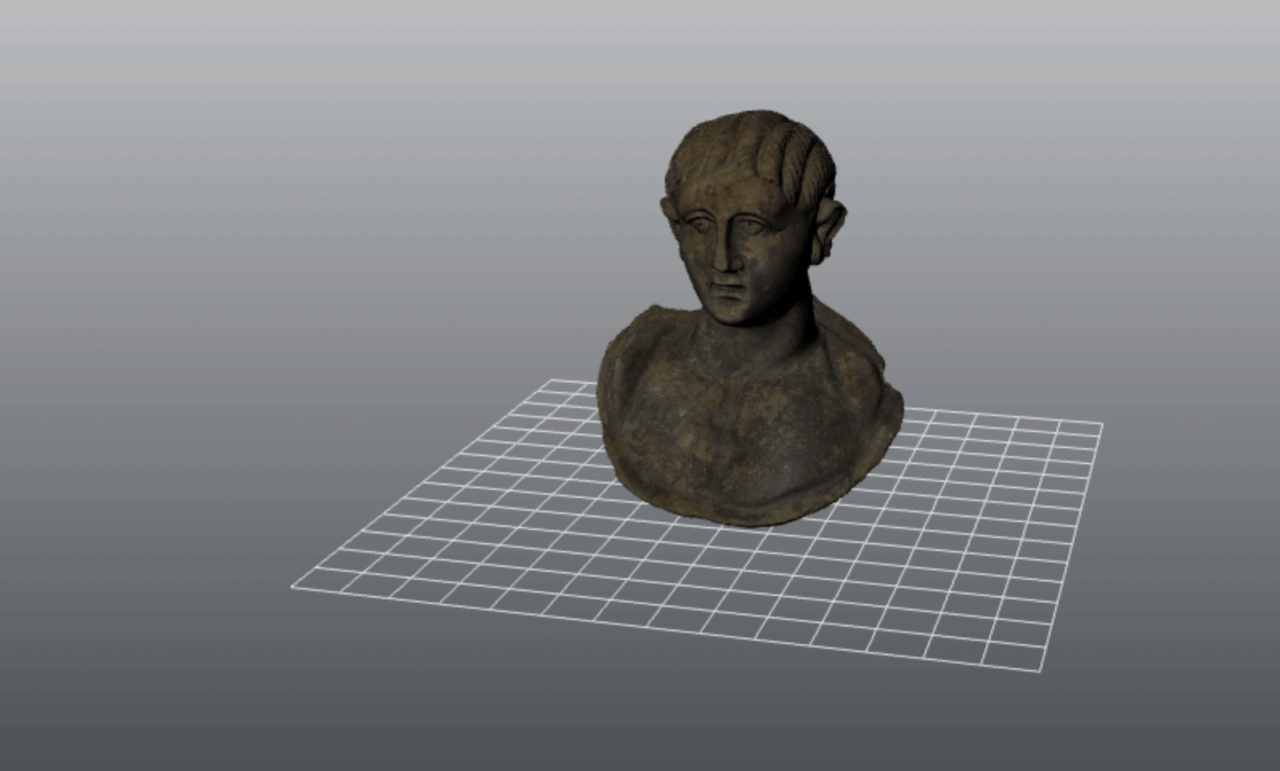

One of the projects that has given me the most satisfaction is Dynamic Collections, a 3D archive for archaeological artefacts, developed in collaboration with the CNR ISTI. Started shortly before the pandemic with a small team, the project has obtained funding and recognition that have favored its exponential growth. Today we are the official point of reference in Sweden for the management of digital archaeological collections. We have gone from collaborating with just the university museum to working with many museums, which regularly send us their objects. Furthermore, the project is entirely open access and is used by students and teachers for teaching.

Other projects that have had a significant impact are the artificial intelligence projects, which have produced extraordinary results in the application of machine and deep learning to the LiDAR, e TETRARCHs, a European project aimed at developing new ontologies to make archaeological archives more accessible and reusable, not only by archaeologists, but also by other actors involved in cultural heritage management.

There is a lot of talk about ethics and 'cybersecurity'. Do you find that the application of these technologies in archaeology has led to new ethical reflections with respect to the traditional principles of the discipline?

Absolutely. Professional ethics in archaeology has changed dramatically in recent years. In the past, the debate mainly focused on colonialism and its implications, a topic that is still fundamental and topical. However, the advent of digital technologies and artificial intelligence has introduced new issues, such as the protection of personal data (GDPR), transparency in information creation processes and access to open data (open data).

For instance, the large-scale publication and sharing of archaeological data poses unprecedented challenges. The case of the 3D scan of the bust of Nefertiti, published without permission in 2016, has opened a heated debate on digital copyright and cultural property. The role of museums is also at the centre of this discussion: on the one hand, their function is to preserve and protect collections; on the other, an overly restrictive approach to data access may result in a form of digital neocolonialism.

The European Union is addressing these issues through policies of open access to publicly funded data. Today, many European projects are obliged to publish results under licences that guarantee their availability. This has led to a new phase in the ethical debate in archaeology. Whereas in the past there was a tendency to repeat already established concepts, today we are faced with new challenges that require equally innovative answers.

What was the path from your PhD at the IMT School that led you to Lund and what skills did you acquire during your PhD that helped you get to this point?

My experience at the School was very stimulating because it allowed me to engage with experts from different fields of cultural heritage, from art historians to architects. At the time, in the early 2000s, this interdisciplinarity was not so common in universities. The IMT School also had great foresight in creating a PhD in cultural heritage technology and management, a field that was still new in Europe. I had the opportunity to do an internship at MIRALab in Geneva, under the guidance of Professor Thalmann, a fundamental experience to understand how research works abroad. I also spent a lot of time at CNR and, thanks to a co-financing between IMT and CNR, I was able to spend the last year of my PhD in the United States, where I wrote my thesis.

While I was there, courses on 'cyber-archaeology' and the digital humanities and I was offered the opportunity to lecture as a junior lecturer. This was an added value when I applied to Lund, compensating for the difficulty of not knowing the language and being younger than the other applicants. Despite the strong competition, the skills I acquired at the IMT School contributed greatly to my selection for the position.

What is the advice you wish you had received when you started your PhD?

In hindsight, I would have found it useful to receive advice on two fundamental aspects: academic writing and handling criticism. Learning how to write an academic article or a grant application is essential, but these are often skills that are acquired over time, through trial and error. Knowing from the start where to publish, how to build an academic network and how to move strategically within the scientific community would certainly have made my journey easier. Another crucial aspect is learning how to deal with the frustration of criticism and rejection. In academia, receiving a negative evaluation on a paper or research proposal is inevitable, but how you deal with these situations can make all the difference. Having a network of colleagues to deal with helps a lot in these moments.

Nicole Crescenzi