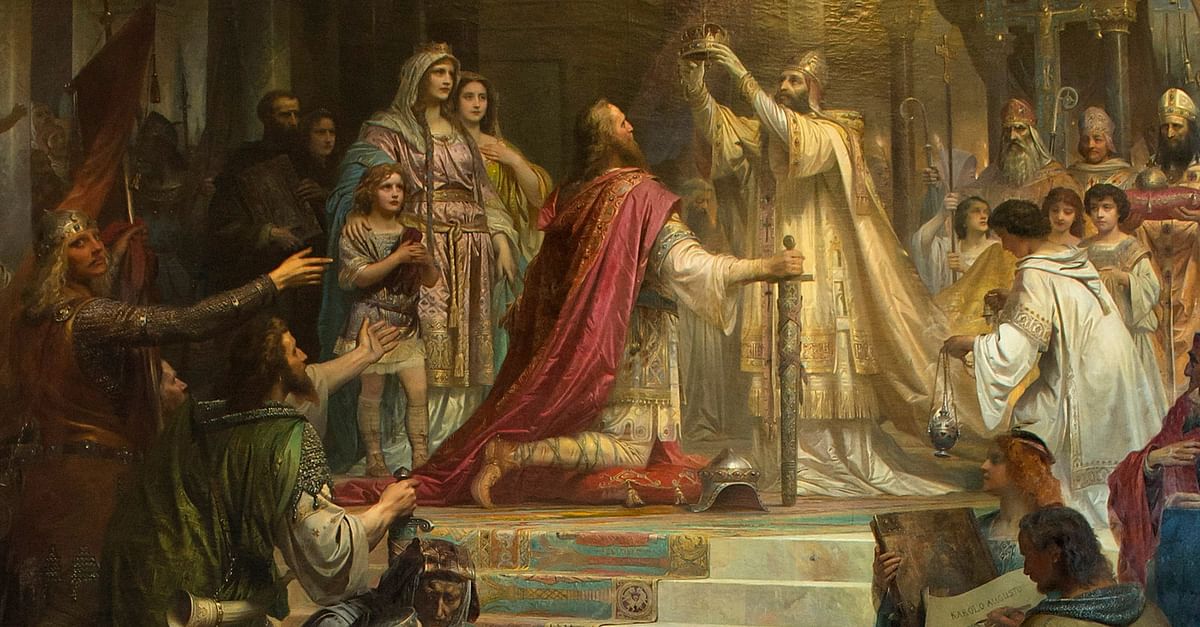

Is it possible to use the rules of a game to study history, to gain a deeper understanding of the functioning of a society and a political system? Gaming, a tool used in many areas of education, can also make a significant contribution to historical research and its dissemination: in short, it can help to introduce the non-specialist public to a deeper knowledge of history. Particularly in the Anglo-Saxon world, this approach is widely used, and has already begun to bear fruit, accompanied by an ever-expanding scientific literature, as the frontiers of application expand, and the questions increase. It was with these considerations in mind, and combining the interest in the application of gaming to history with that in the specific historical period under consideration, that I decided to proceed with the conception of a game model that could 'show' its players how the political system that existed in the late Carolingian Empire (encompassing roughly the second half of the 9th century) worked.

Playing feudal lords

First of all, a step back: when we speak of a 'medieval political system', what do we mean? The first thought of many (and not just the uninitiated!) goes to what is conventionally called the 'feudal system'. Due to its centrality in medieval history and medievalist research, the feudal system has certainly not escaped the attention of the gaming world. Among video games, one of the best examples of historical popularisation of the feudal system (here deliberately understood in a generic sense), both in terms of circulation and the quality of the result achieved, is the series Crusader Kings (now in its third edition). But even the board game was not left out of the challenge: commercial games such as Fief 1429 (in no less than two editions) and, to a perhaps lesser extent (and geographically and chronologically more circumscribed), Medieval Conspiracytried to give their players a 'taste' of how a feudal system could work.

Historical confusions

Yet, the Middle Ages is not just feudalism, and to be excluded from commercial interest, and even from specialized interest as a possible scope of the gamingwas precisely that political system that not only preceded feudalism as we know it, but also, in part, created its preconditions: the political system of the Carolingian Empire. All too often feudalism and Carolingian Empire are still confused, especially in schools. Who does not remember the first appearance of the (which never existed) 'feudal pyramid' just when Charlemagne and his successors were mentioned? Or again: the first appearance in the school textbook of 'dukes', 'counts', and 'marquises', the real 'magic triad' of scholastic feudalism? Nothing could be further from historical reality. Decades of historiographical research and debate have helped illuminate the workings of the Carolingian Empire, and show how wrong it is to consider it the place (and time) where 'classical' feudalism first appeared. The Carolingian and late Carolingian political system, in particular, was based on assumptions that were partly divergent from those of the feudal system that was to develop in the following centuries. Some of these assumptions can be transposed within specific game mechanics, which can thus form the skeleton for an actual game describing their functioning, and which can also be used for further research and refinement of the analysis. What are these assumptions?

The rules of the game

- The relationship with the sovereign was a fundamental vehicle for the preservation, increase, and transmission of the power of the individual members of the Carolingian elite through the allocation of offices and titles. In other words, every member of the Carolingian elite, if they wanted to preserve their position, needed to keep themselves close (often literally) to the sovereign.

- Linked to the previous point: the importance of having sovereigns 'at their disposal', who could legitimately offer offices, titles and honours to members of the elite.

- Many kingdoms, one empire: despite the existence of different sovereigns (think of the well-known Charles the Bald, Ludwig the Germanic and Lothair, the sons of Ludwig the Pious) the idea of one empire (and one emperor) remains.

- Dynastic legitimisation: not everyone could be king, but only members of the Carolingian dynasty. When this direct relationship between kingship and dynasty came to an end (at the end of the 9th century), imperial unity also came to an end, and the kingdoms of feudal Europe that we all know (France; Holy Roman Empire; etc.) began to emerge.

Obviously, these four points do not aspire to be exhaustive. Every political system is an extremely complex, multifaceted structure, and varied according to the times and places in which it takes place, and the Carolingian political system is no exception. However, they are sufficient prerequisites for a game mechanic to be built upon them. The prerequisites are all there: several players in constant interaction with each other (the various Carolingian and post-Carolingian sovereigns); rules that apply to all, and which end up determining the dynamics of the game itself (the need for the nobles to have 'space' as close as possible to the sovereigns, and for the sovereigns to have as many nobles as possible at their disposal, in order to maintain their consensus); a common goal, the imperial crown (and the need, therefore, to keep the empire intact as much as possible, despite the clashes between the contenders).

Unlike the game mechanics based on a 'classic' feudal system, the key resource is no longer territory (according to the equation that the more territory one possesses, the more powerful one is), nor of course currency, but rather the different members of the Carolingian elite themselves, with the ability to attract and keep them, and to 'use' them in the most efficient (and least risky) way possible.

Change the research? It also changes the game

All these dynamics can, of course, be realised in the form of either a video game or a board game. The latter option enjoys, however, a not inconsiderable advantage, should one wish to use the game as a tool for research and analysis, especially by university students and specialists, but not only: the possibility of being easily modified. Modifying the game mechanics in fact amounts to deciding to emphasise one element rather than another. In other words, when the player/student proposes a modification to the game, they are placing themselves in the same position as the author and, just like the author, they are proposing their own reading and interpretation of the subject matter, the result of their own learning work. To give an example, taking up the theme of the game proposed here, i.e. the late Carolingian political system, a player might consider it more important to emphasise the relations between the Carolingian aristocrats and the territories over which they exercised their jurisdiction and in which they enjoyed relations of pre-eminence. Or yet another player might feel that the effects of the Viking raids, which played such a large part in the history of the empire, have been unduly neglected, thus proposing a mechanic that introduces them into the game. And so on.

This whole discourse is just one example, in turn, of how powerful the game tool can be when combined with the aims and tools of historical research.